It all started about two and a half years ago when my buddy the writer Hartford Gongaware turned up in my hometown of Greenville, Mississippi, with some filmmakers who were documenting life in towns along the river. Greenville is a river town (well, sort of—a while ago the river changed course and now we’re technically on an oxbow lake called Lake Ferguson, but if you get in a boat at the foot of Main Street, the Mississippi’s only about six miles away). Anyway, the camera people needed some footage on the water, and my friends Hank Burdine and Howard Brent offered up their boats for an outing. Because it was the day after the first annual Delta Hot Tamale Festival, there were a lot of people in town, including my Garden & Gun colleague Roy Blount, Jr. and his wife, the painter Joan Griswold. Naturally, we all decided to go along.

Now, that in itself is not unusual. Pretty much everyone I know in Greenville grew up on a raft or a speedboat or both—we even have a Yacht Club, though to my knowledge only one yacht has actually docked there in its seventy-some-year history. Hank is a commissioner of the Mississippi Levee Board (founded in 1865), and Howard once ran one of the biggest towboat companies in the country (founded by his father, Jesse, a former deckhand, in 1956). We’ve all spent countless hours water-skiing, tubing, drinking, fishing, and generally engaging in the maritime version of that eternal high school preoccupation “riding around.” But this time, we had a destination. We loaded up the boats with buckets of chicken and lots of beer and Bloody Marys and headed straight for an enormous sandbar Hank had found just under the new Jesse Brent Memorial Bridge that connects Mississippi to Arkansas.

Everyone agreed it was magical. On our own private island, we had the freedom of Huck and Jim without the bad guys—if you don’t count the evil Asian carp that jumped in the boat and slimed one of the cameras. We ate and drank, and Joan made really cool sculptures out of driftwood. We took dips in the river and lay in the sand and headed back just before sunset beneath a buttermilk sky.

It was already pretty perfect, but since then, our outings have gotten a tad more grandiose. In our second year, we were joined by Bo Weevil, a.k.a. Sid Law, who has a welded aluminum boat custom made with a flat bottom, high gunwales, and an eight-foot beam on which he has run the entire length of the Mississippi, Missouri, Tennessee, Arkansas, and Atchafalaya Rivers. “Like mine,” says Hank, not entirely tongue in cheek, “it was designed exclusively to run safe in the river carrying lots of people, whiskey, and fried chicken.”

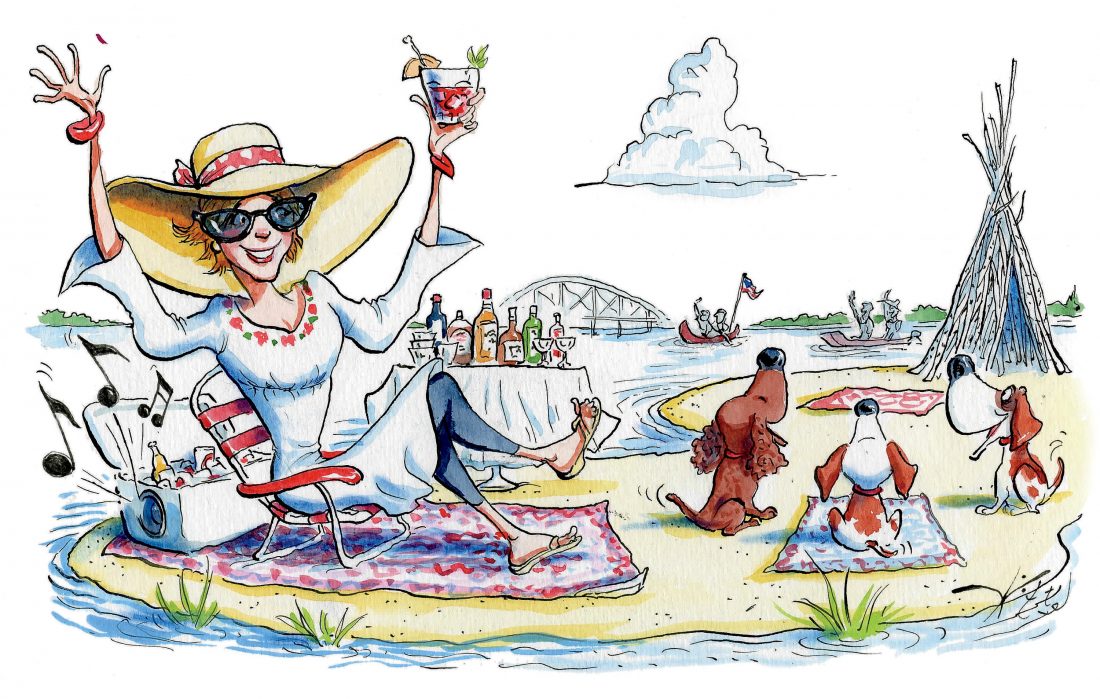

Bo’s boat enabled us to tote more people, but also tables and lounge chairs and a slightly more elaborate menu. There was a full bar and a bartender and a ladies’ room in the form of a tepee made from willows cut on the opposite bank. Tunes were provided by the official Sandbar Boombox, a masterpiece of Burdine engineering consisting of an ice chest with holes cut in one side for speakers and a car CD player installed on the inside and rigged with twenty feet of wire attached to a 12-volt battery with alligator clips. There was live music, too, provided by the exceptionally talented Brent sisters, Jessica, Eden, and Bronwynne, who all brought their guitars, and Howard, who never goes anywhere without his famous miniature harmonica.

These days, we don’t bother to wait for the tamale fest to make a trip, but we do have to wait for the river to go down. (After Hank and I scouted a sandbar for a planned trip last May, the river rose six feet in a single day, which meant that it disappeared.) Also, we keep adding stuff: Indian quilts, folding love seats, threadbare Oriental rugs. Hank tops a charcoal-filled hole with a grill in order to cook his sublime duck poppers, and I use it to heat up a big enamel casserole of barbecued pork shoulder. Paper plates and Solo cups have given way to enamel plates and stemmed Lucite glasses. We even have a signature drink, a punch called the Evening Storm (an event we’ve so far avoided) invented by Christiaan Rollich, the talented bar manager at Suzanne Goin’s Lucques and A.O.C. in Los Angeles, after I told him about our exploits and sent him an image of the painting of the same name by David Bates. (At A.O.C., the hostess’s mother is from Wilmot, Arkansas, just on the other side of the aforementioned bridge—the world is small, though you could never tell it from our sandbar vantage point.)

On our most recent visit last fall, the river was so low there was plenty of room for dancing. Eden Brent, the piano virtuoso and three-time Blues Music Award winner, played “Fried Chicken” and “Panther Burn” in her usual performance garb, including a black sequined porkpie hat purchased in the Memphis airport, and lamented the lack of a sandbar keyboard. Our friend Raymond Longoria, who had performed at the tamale fest the day before, had brought his guitar, but not his accordion, at which he excels, so he vowed to return with it next go-round. There were no spoons, so Jessica showed off her prowess with a pair of forks (who knew?). At one point, we hatched a slightly sodden plan to bring out an old upright piano and leave it until the river carried it away the following summer. The next day I got a text from Hank: “Not possible to get an upright on the sandbar. WAY too heavy to transport, but we can do an electric keyboard with a small quiet Honda generator and long cord.”

If all this sounds insanely over the top, we come by it naturally. The Mississippi Delta, which is actually the diamond-shaped alluvial floodplain of the Mississippi and Yazoo Rivers, was all but uninhabitable until well into the nineteenth century. Lured by some of the richest soil in the world, planters whose land had already been tapped out in places like South Carolina and Kentucky took a gamble and battled panthers and floods and a tangled mess of a hardwood forest before they could even think about dropping a seed into the ground. Once they did, the results were worth it economically, but there wasn’t a whole lot to do there, so they became extremely adept at making their own fun. Most of which involved a serious intake of whiskey and traveling long distances over rough terrain—in 1850, fewer than 25,000 people inhabited the Delta’s 7,000 or so square miles, and this being the bad old days, the majority of them were slaves. House parties abounded.

These days the population of the Delta is more than 500,000, and there is all manner of things to do, but old habits die hard and we persist in organizing elaborate diversions. I mean, there may be plenty of people, but the mosquitoes and snakes haven’t gone anywhere, and it remains hot as hell. Still, there are only so many ways to skin a cat, which is why I can’t believe it took us so long to come up with the sandbar as a venue.

Especially since I am apparently no stranger to sandbars, something I was reminded of in a post on my Facebook page a year or so ago by a former bartender at the late and very much lamented One Block East. During what we shall call my formative years, the Block (so called because it was located one block east of the levee) was the primary source of almost every diversion a girl could find. I myself had not planned on sharing any of them—ever—but one day a former assistant checked my page and began reading aloud: “Hey Julia, it’s Sam here. Remember that time we stole the DDT’s boat and you and Robbie left Finn and me on a sandbar until like five in the morning?” Well, sort of. Sam was a bartender at the Block whom I hadn’t heard from in more than thirty years, and the DDT is the Delta Democrat-Times, whose then owner, Hodding Carter III, kept a very handsome speedboat docked within walking distance of the bar. Finn is Hodding’s daughter, and she knew where the keys were hidden, and Robbie was another bartender with whom I was ridiculously in love. Suffice to say that this is why Facebook scares the hell out of me. Also, my memories are not nearly as clear as Sam’s. For example, I have no idea where Robbie and I went while leaving our companions stranded, but I can only hope we found another sandbar and smooched.

It is a miracle that I lived to see another sandbar in the daylight, but I’m extremely grateful that I did. On that last outing, we’d just started unloading the boats and setting up the food tables when a thirteen-foot canoe, outfitted with a tattered American flag and containing two very sun-brown young folks, came within our line of sight. We are used to seeing the occasional towboat, and in the old days we’d get a lot of hippies on handmade rafts, most of whom ended up composing the kitchen staff at the Block. But I’m not sure I’d ever seen such a comparatively tiny vessel, especially one that started off in Indiana.

The intrepid canoers, Susan and George, were on their way to Baton Rouge, where they planned to sell the boat and head back north. When we met them, they’d been on the river for more than two months, camping out on sandbars and making infrequent trips into towns for supplies. When they came upon our own elaborate “campsite”—not to mention Hank waving his arms, hollering “Cold beer! Cold beer!”—they must have thought it was a mirage.

They stopped anyway and turned out to be the loveliest of guests. Among Susan’s possessions was a beautiful six-string guitar stored in a black plastic garbage bag, and she played a song she’d been composing on the trip. We fed them catfish pâté and barbecue, and then Bo Weevil insisted that he put them up for a few days, promising to drive them and the canoe down to Vicksburg so they could make up for lost time. We showed them around the Delta and invited them to a dove-hunt breakfast and shared all the other diversions we had mastered. They later wrote really nice things about us on their own Facebook page (one on which I came out a lot better), but they did more for us than we did for them. Our encounter reminded us again of the river’s mythical but no less real place in American life. It allows for reinvention and renewal, and enables—encourages, really—our citizenry to light out for parts unknown. In our case, new territory is just a twenty-minute boat ride away, but it feels like another world entirely and it makes for a damn fine day.