Land & Conservation

Dwight McCarter: The Tracker

During his thirty years tracking lost souls through the Smokies and beyond McCarter rescued twenty-six people, many of them children. These days he’s still in the mountains, often thinking about those he found—and the few he didn’t

Photo: Erika Larsen

The last lost boy he found was named Phillip Roman. Phillip, who was ten years old, had wandered away from his family while they were at Clingmans Dome, the highest point in the Smoky Mountains, and as happens more frequently and more suddenly than you could ever imagine, he simply seemed to disappear. This was in the summer of 1994, and Dwight McCarter, who had been a backcountry ranger for almost thirty years and was just about to retire, was called in to track him. Phillip had been lost for three days by then. “I’d been away for the first two,” he tells me. The authorities took McCarter to the Point Last Seen—or PLS, in ranger jargon—and showed him three different tracks. The first set of tracks was a bear. “I knew it was a bear in half a minute, but they wanted me to follow it to be sure, and the farther I did it just got more and more bear.” The second set of tracks was a bear, too. “But the third set of tracks belonged to Phillip,” he says.

Listening to McCarter tell a story is to understand why stories are told: It’s a rush, the sound his sentences make, the voice his words come to me on. It’s better than a book.

“So we set out into North Carolina,” McCarter says. Phillip didn’t know it, of course, but he’d left a clear trail for McCarter to follow, signposts almost. McCarter knew Phillip was right-handed, “and when a limb came to him, he’d break it forward with his right hand. You’d do the same thing. The broken branches pointed to the direction he’d gone.”

They came to a small waterfall and saw that the tracks on the other side of it had changed: One foot was dragging now. “He’d fallen off the waterfall,” McCarter says. “Not enough to kill him but to hurt him pretty bad.”

Phillip could not have gone far up the ridge. McCarter had the men fan out across it, working in a zigzag path up the hill to the top. The plan was to make multiple sweeps, but it didn’t take long for one of the men to holler, “Dwight, over here! Someone’s talking to me from a bush!”

That was Phillip, hiding away in the shadowy green of a rhododendron thicket, the last of twenty-six people Dwight McCarter found.

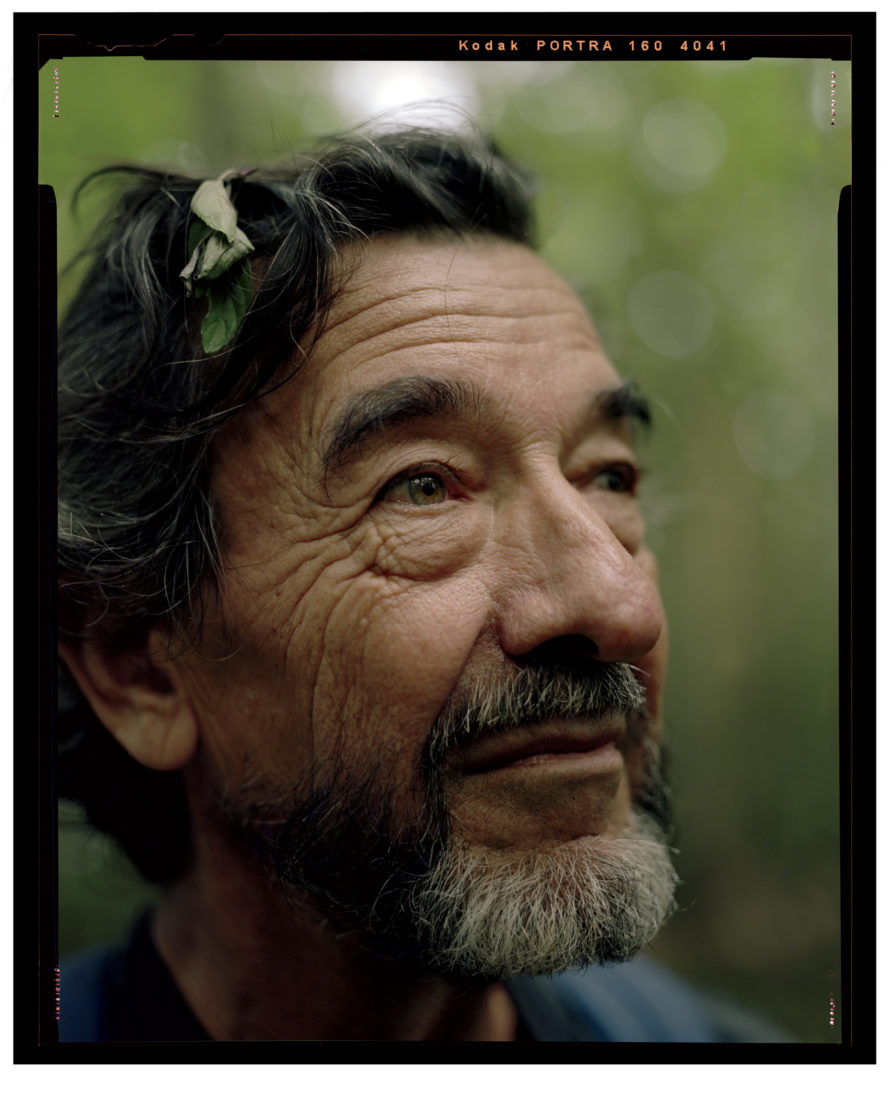

McCarter is sixty-nine years old now. He has kind, intelligent eyes and a Lincolnesque beard, lightened by gray. He’s thin, sturdy, but not tall, and when he’s telling a story—which is what he does, really, from the moment you meet him until the moment you’re gone—the tenor of his voice sweeps up and down the tonal register, from a baritone to a falsetto twang in the course of a single sentence, or even a two-syllable word. He laughs a lot, the kind of laugh that begs for company and gets it. He is amused by people, history, and nature itself.

He was two years out of the army before becoming a ranger, in 1967. His first job was a seasonal position, manning fire towers. It was a job he loved. During fire season he’d sit in a cane chair on top of the tower and watch for lightning strikes, then he’d map the strike, “run a line out to it,” and they’d check the position out for smoke. But he wasn’t long for the tower. He had skills other rangers didn’t, and still don’t.

McCarter can track a human being.

VIDEO: ON THE TRAIL WITH DWIGHT MCCARTER

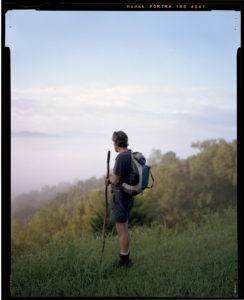

Photo: Erika Larsen

McCarter in his element.

It’s not hard to get lost in the Smokies. “It’s boys, mostly,” he says. “Young boys. Hardly ever girls. Girls stick close, but boys run ahead, take shortcuts, hide to jump out and scare everybody.” For about a quarter of a century when someone in the Smokies was lost, McCarter was asked to find them. And he generally did, but not always, and not always in time. His domain comprised 521,000 acres and more than 800 miles of trail.

McCarter and I spent a fall day together on the trails surrounding Blackberry Farm, the luxury Smoky Mountain resort where McCarter has worked as a guide, naturalist, and storyteller since 1979. It’s not far from Townsend, Tennessee, where McCarter has lived his entire life. It’s never been a full-time job—he did it on his off days from the National Park Service until he retired from that, in 1994—but McCarter enjoys showing people a world that, even when it’s right in front of them, they can’t see. Me, for instance: We’re hiking lazily down a trail for fifteen minutes before I realize we are tracking a bear.

“There she is,” he says. He kneels, and picks up the smallest of twigs. It’s freshly broken. The toothpick-size twig itself is a slate gray, but where it’s broken is white. A dot of white, no bigger than a bread crumb.

“This is how I find the children,” he says. “I look for the white. This tells me where they went.”

Photo: Erika Larsen

Natural Patterns

A Gorgone Checker-spot at rest.

Now I can see it, a shadow in the dark soil: the heel and the claws of a bear. Still looking at the print, he says, “She came down the mountain and stopped here at the trail, looking left and right for danger, for humans, then jumped over the trail. No prints here, see. Big bear, too. Three hundred pounds. Probably came through last night around 3:00 a.m. or so. Coming down the mountain for water, you know. Usually they keep going straight, but here…she angled off. That leaf is bent, there, and you can see the underside of the leaves of that branch over here. She was in a hurry.” He crumbles some of the dirt between his fingers. “Seen this track before. She’s always by herself. No babies. She’ll probably live to about sixteen and die alone. Sad. But maybe she just likes being by herself.” He laughs and suddenly it isn’t that sad anymore. “Or maybe she just has a bad personality.”

McCarter doesn’t just track: He constructs a narrative about what he’s tracking. It’s not just about what happened, but why it happened, and what happened before it happened that made what happened happen. Of course, there’s no way either of us will ever know for sure if he’s right about the bear. But I take his word for it.

Bears are plentiful in the Smokies. They probably won’t kill you, but if you’re lost and die by some other means, after three days or so they will probably eat you. Bears drag their quarry uphill to a ridge and cover it with dirt and dine on it slowly, over the course of a couple of weeks, coming down for water and then returning, until all that’s left of a person are brass shoe eyelets, belt buckles, keys, caps, vertebrae. “Every year that passes without finding the deceased, another inch of soil will cover the remains,” McCarter says. “A man went missing in 1998 and then was found in 2004. Under six inches of earth.”

Photo: Erika Larsen

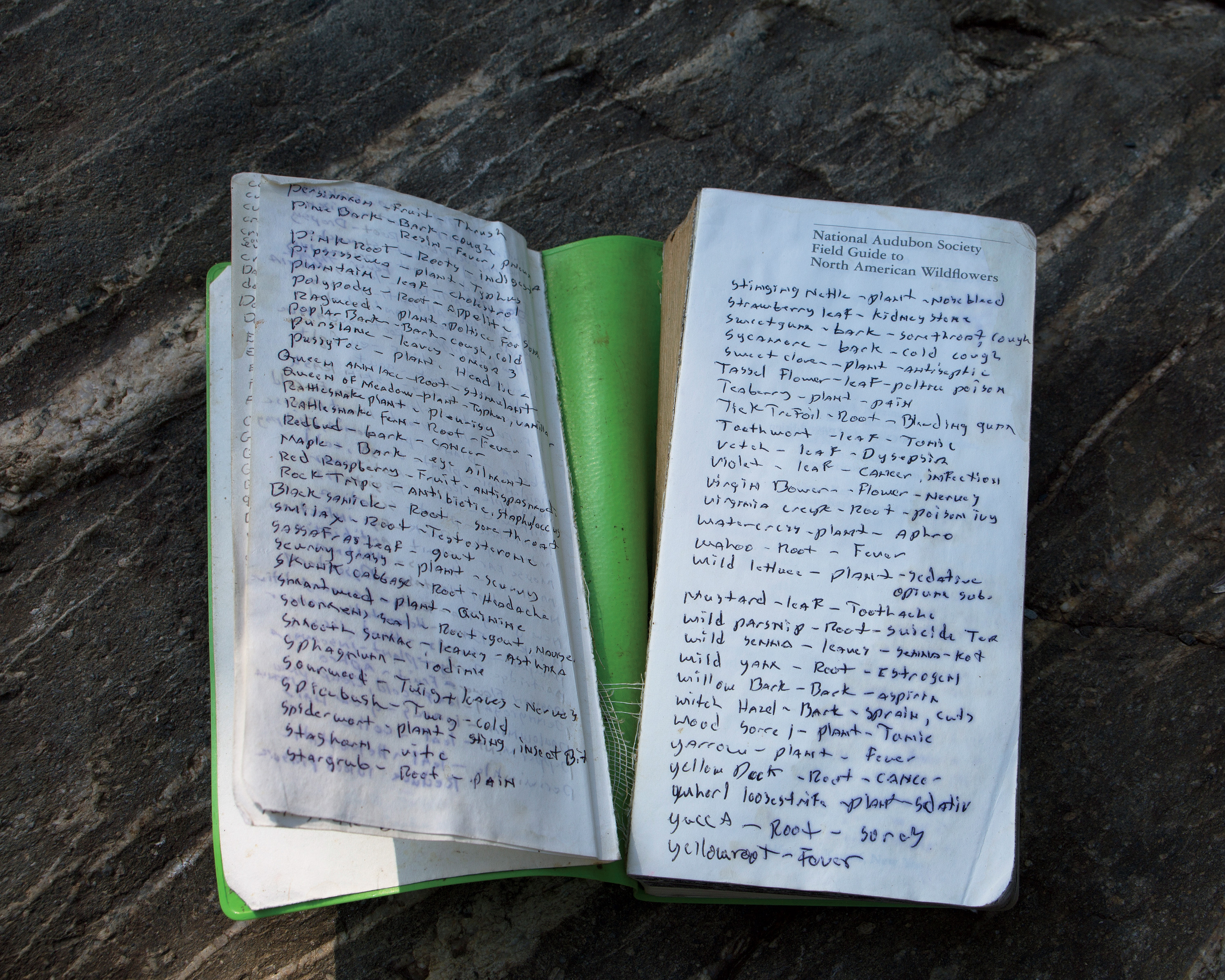

Pages of personal notes from years spent in the woods fill McCarter's field guide.

But sometimes the lost stay lost forever. In 1969 a six-year-old boy named Dennis Martin wandered away from his family and minutes later was gone. It was 4:30 in the afternoon. His family immediately started calling out to him and scouring the woods around where he had last been seen. Nothing. Five hours later a massive storm blew in, and the rain was cold, and the woods were dark, and Dennis was out there in it, wearing a T-shirt and shorts. Over the course of the next three weeks more than a thousand people, including members of the Green Berets, along with Dwight McCarter, searched for the boy. They never found a trace.

When McCarter talks about Dennis Martin, he speaks slowly, he chooses his words carefully, and there’s a ghost in his eyes.

Everything in the forest has a name, and McCarter knows the name of everything. But it’s more than that: He knows the story behind the name. His grandmother taught him a lot of what he knows; the rest he picked up along the way. His recall for names and dates stretching back centuries is astonishing. An hour into the hike he’s touched or pointed at half a dozen plants and told me something like Now, this bush here is called a doghobble. A bear runs right through it, but it has so many limbs a dog’s legs get tangled up in it. This is poison ivy, of course, but look here just three feet away: jewelweed. That’s the cure for poison ivy. When nature hasn’t been messed with, the cause and the cure are usually close together. This big-leafed tree? It’s a kind of magnolia, but I like to call it the Charmin Tree, because the tops of the leaves are so soft and they’ve got quinine in them, you know. So it’s good to keep a leaf or two in your back pocket just in case.

He sees things I don’t see. Somehow he spots a furry orange ant scurrying through the underbrush—a cow killer, he tells me. Crawls in a cow’s ears and kills it. And on we go. It’s spooky, how much he fathoms about the world, everything he understands, how it works and how he makes it work for him. I bet he knows a secret whistle that would bring all the creatures of the forest to his side in a heartbeat. I wouldn’t be surprised.

Photo: Erika Larsen

McCarter uses jewelweed to lessen the itch from poison ivy.

It’s been a few hours now and we’re back on Blackberry Farm. I’m tired. McCarter pinned a sprig of mint to my baseball cap when we started out—“It keeps the gnats off,” he said—and the mint looks like I feel: wilted. We find a picnic table and eat a box lunch the Farm provided for us. It’s good: a biscuit, chicken, some peas, a cookie. Water. But we’re not there five minutes before I look down and see that a polite line of ants has already found us. They’re crawling through the planks in the table and having their way with my biscuit crumbs.

Like seemingly everything else in the natural world, these ants delight Dwight McCarter.

“See how they’re finding your food?” he says. “They’re following a formic acid trail. When they’re on the trail, it’s easy—they just crawl right to it.” Then he brushes some of the crumbs away and the ants scatter in disarray, as if suddenly blind. We watch them for a few quiet moments. “This is what my grandmother taught me when I was a boy. When I lost something she said, Act like an ant. Circle out from the place you last saw it, looking in wider and wider circles, and then zigzag back in, until you find what you’re looking for. For the ants it’s formic acid; for me, it’s the white.”

Which is how he’d found Phillip: circling out, zigzagging in.

Photo: Erika Larsen

His well-worn hiking boots.

“Hey, Phillip,” McCarter said to the boy that day in July 1994 who was still peering out of the rhododendron. “Are you okay?”

“No,” Phillip said.

Phillip was cold and hungry, and his ankle was torn up. McCarter brought him out of the thicket and heated up a little Tang in the bottom of a cola can for him, and Phillip kept that down but not much more. They sat there for a while and talked. They splinted his ankle. McCarter got his mother and father on the two-way radio, and Phillip told them he was okay. McCarter said, “One of the other rangers is going to carry you out of here, Phillip, and I doubt I’ll ever see you again. So I want to ask you. Do you have any questions as to what happened to you here these last three days? Anything that made you scared? Because we need to get it over with. You don’t want to go back to Florida and live with something that’s going to haunt you for the next fifty years. We need to put a name to it right now.”

The boy nodded. “I have questions,” Phillip said. “Late at night I’d be sleeping in the leaves and hear this rustling sound all around my head, something moving through the leaves. What was that?”

“That’s a deer mouse,” McCarter said. “Loves to come around people, and it gets in your ears and pokes around some, but it won’t harm you, not at all.”

Phillip nodded, taking it in. “And then,” he said, “after it got dark I’d hear these loud sounds, like something breathing, hard, not far away from me.” And Phillip made the sound he thought he’d heard.

“Now, that was a deer, probably,” McCarter said. “They blow at each other sometimes if they’re mad. But it’s just to each other. They never would have harmed you. Anything else?”

Phillip shook his head. “Nope,” he said. “I think that’s it.”

When I was ten years old, I had a prayer framed and hung on the wall above my bed.

From ghoulies and ghosties

To long-leggedy beasties

And things that go bump in the night

Good Lord deliver us!

Ghoulies and ghosties and long-leggedy beasties is exactly what they are until someone like McCarter comes along and gives a name to the unknown, setting you straight. Turns out it’s just mice and a couple of angry deer, and everything’s going to be okay.

McCarter and I watch the ants find the acid trail again, and we sit there like that for a while.

Photo: Erika Larsen

Striking off into the mountains that surround Blackberry Farm.